The relationship between Portugal and Angola is one of the most intense and complex in all of Portuguese colonial history. Their link has been an open wound for centuries, a cycle of domination, resistance, war, separation, and, finally, reunion. Angola was the colony that took Portugal the longest to leave. And perhaps for this very reason, it is today the African country with which Portugal has the deepest, most visible, and most contradictory ties.

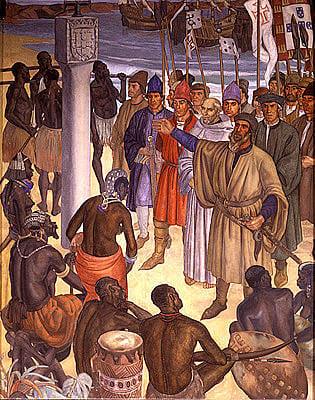

The First Contact

The story begins in the 15th century, when Portuguese navigators reached the Angolan coast. In 1482, Diogo Cão reached the mouth of the Congo River. From here, the Portuguese began relations with the Kingdom of the Congo, a structured civilization with political power, an army, religion and an economy. The first contact was diplomacy and trade. But it didn’t take long for interest to turn into conquest.

The evangelization of the Congolese people, led by Catholic missionaries, went hand in hand with the imposition of the European model. African kings converted to Christianity, took on Portuguese names, and adopted European costumes and rituals. But behind the cross came the sword. And behind the incense, the smoke of the slave trade.

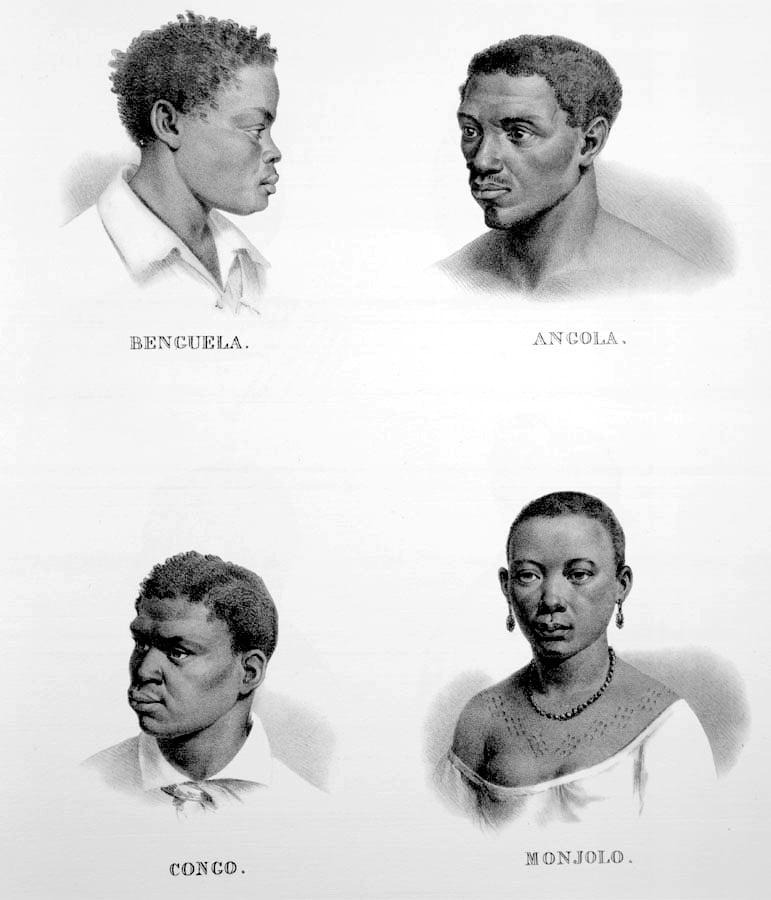

For more than three hundred years, Angola was one of the main export centers for African slaves to Brazil and other colonies. Millions of men, women and children were captured, sold and shipped off to a fate of suffering. Luanda and Benguela became central hubs for this brutal trade. Portugal, as a nation, enriched itself with this system, and the wound still bleeds today in the collective memory of both countries.

Modern Colonialism

With the end of slavery in the 19th century, Portugal redefined its presence in Angola. The so-called “modern colonialism” began. Instead of the slave trade, the land and population were controlled through direct administration. Portuguese planters settled in Angola, occupying vast regions with plantations of coffee, cotton and other export products. Forced labor continues, now disguised in the form of contracts and obligations imposed by the colonial administration.

During the first half of the 20th century, resistance movements to the Portuguese presence were stifled with violence. Repression, censorship, and the marginalization of the local population intensified the feeling of revolt. And while Portugal sank into a dictatorship led by Salazar, Angola simmered under the surface.

The Colonial War and the Road to Independence

In 1961, war broke out. First in Angola, then in Guinea and Mozambique. In Angola, several armed movements emerged: the MPLA, UNITA, and the FNLA. Portugal, with an ill-prepared army and a fragile economy, entered a prolonged conflict that lasted more than 13 years. It was a cruel war, fought in jungles, villages, and in the hearts of a divided people.

The colonial war was not just a battle between Portugal and the liberation movements. It was also a civil war in disguise, with different factions fighting for future power. Above all, it was an unjust war, in which thousands of Portuguese soldiers, many of them boys from villages in the interior, died without knowing why.

The Carnation Revolution, on April 25, 1974, marked the end of the dictatorship in Portugal and paved the way for the independence of the colonies. In 1975, Angola became a free country. But freedom came with pain.

Civil War and Post-Colonial Relations

Independence did not bring peace. The country was plunged into a violent civil war between the MPLA (supported by the USSR and Cuba) and UNITA (supported by the USA and South Africa). For more than twenty years, Angola was a battleground for foreign interests, with destroyed cities, millions of dead, and an exhausted people.

Portugal, fresh from its own revolution, maintained an ambiguous position. On the one hand, it was trying to distance itself from its colonial past; on the other, it had deep economic and emotional interests in Angola. Many Portuguese remained in Angola after independence. Many Angolans migrated to Portugal, creating a link between the two territories that has never been broken.

The Portuguese-Angolan Community and Current Challenges

With the end of the civil war in 2002, Angola entered a period of reconstruction. Portugal once again became a privileged partner. Portuguese companies took part in rebuilding infrastructure, exploiting natural resources and training staff. Portuguese (or Luso-African) culture made a strong comeback: music including literature, gastronomy, and television. Lisbon and Luanda have become sister cities, with daily flights, mixed families, and cross-business.

But the relationship is also marked by tensions including cases of corruption, political disputes, and economic inequalities. Many Angolans feel that Portugal continues to act like a paternalistic former metropolis. Many Portuguese see Angola as a place of lost opportunities and hope for more recognition of the Portuguese contribution. The relationship remains alive and vibrant, but also fragile.

Places in Lisbon where the Angolan Presence Can Be Felt

Martim Moniz and Mouraria

Neighborhoods where African communities, especially Angolans, live, work, and celebrate. Here, Creole mixes with Portuguese, the smells of muamba and funge meet the sound of kuduro. It’s an African Lisbon, alive and real.

Aljube Museum

Dedicated to the resistance to the Portuguese dictatorship and the struggle for freedom in the former colonies. It has sections dedicated to the colonial war, censorship, political prisoners, and African liberation movements.

Afro-Portuguese Cultural Spaces

Venues such as Espaço Espelho d’Água, Casa Mocambo or B.leza promote Angolan culture in Lisbon through concerts, exhibitions and gastronomy. They are meeting points where the present and future of Lusophony are celebrated. There are also a number of Angolan restaurants in Lisbon as well that serve delicious Angolan dishes.

Final Thoughts

Portugal and Angola share a long and painful history. What began with conquest and slavery became a relationship of war and resistance, and later a complex bond full of affection and resentment. Today, you can see this history reflected in the streets of Lisbon, in the songs that play on the radio, and in children’s first names.

The wound is still there, but it’s now a scar. Visible, permanent, but it can be touched without pain. And perhaps this is precisely why the relationship between Portugal and Angola is one of the most human, most real, and most future-oriented in the whole of Portuguese colonial history.