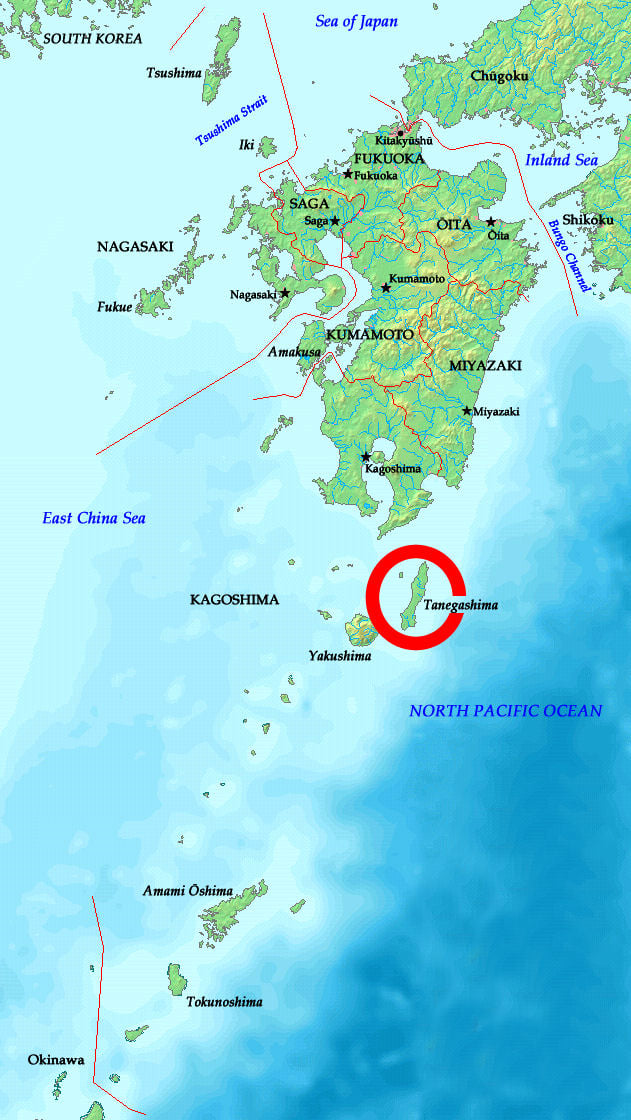

The history shared between Portugal and Japan reads like an epic saga, an intricate web of exploration, trade and cultural exchanges that defied the limits of oceans and empires. This story begins in 1543, on the windy shores of Tanegashima, where Portuguese traders first set foot on Japanese soil. These first encounters were the spark that would ignite centuries of interaction, laying the foundations for a relationship as complex as the folds of a kimono.

The Age of First Encounters

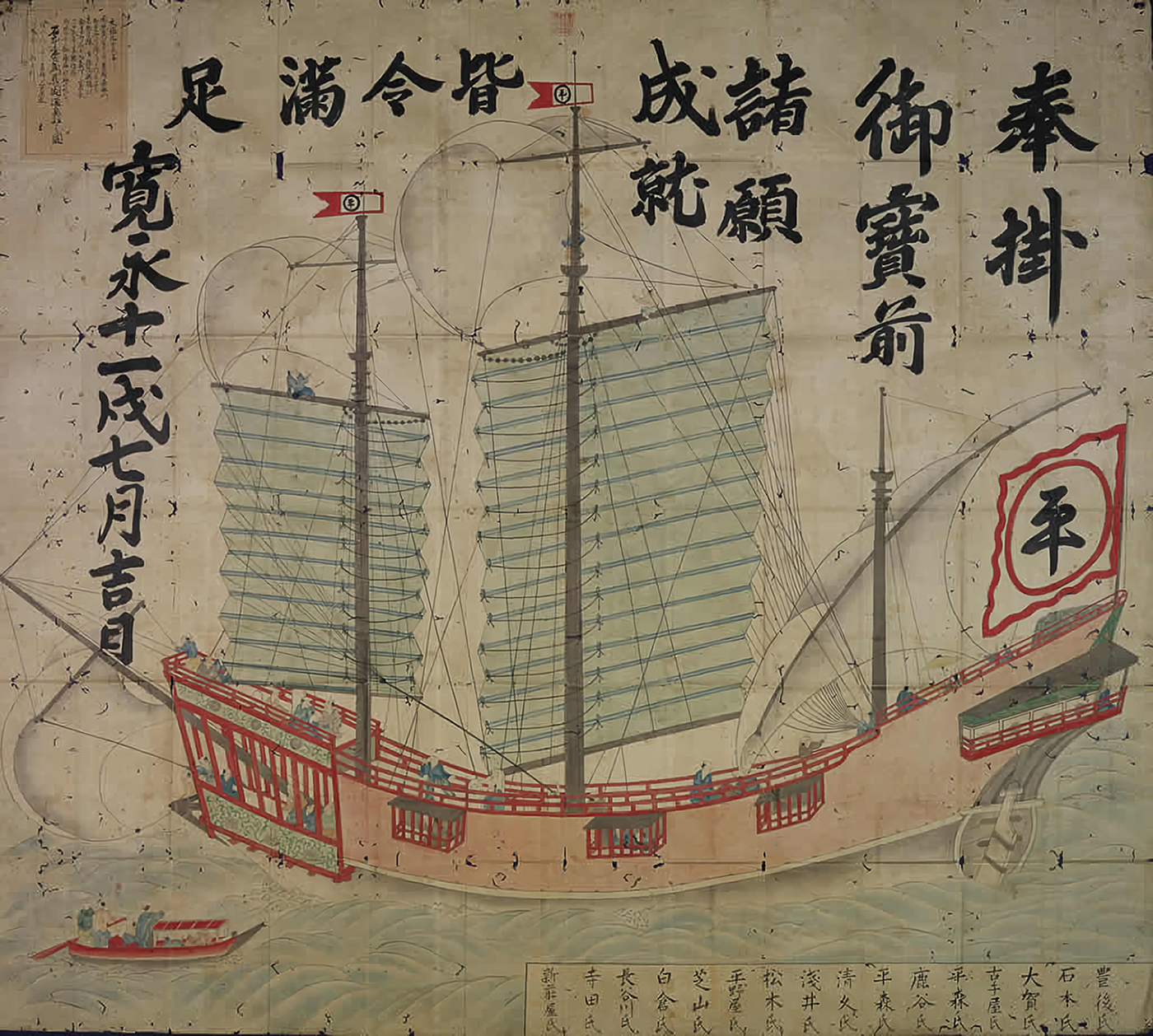

The sixteenth century was a time of discovery, and Portugal – a nation of daring navigators – was at the forefront. Driven by a thirst for adventure and wealth, Portuguese navigators had already mapped vast regions of the globe when their ships were diverted to Japan. The meeting of these two cultures would indelibly change both cultures. For the Japanese, the Portuguese brought not only goods but a glimpse of a wider world. Firearms, specifically mecha muskets, were among the first items introduced, forever altering the Japanese military landscape.

But it wasn’t just about weapons and trade. Portuguese Jesuit missionaries, led by figures such as Francisco Xavier, ventured into Japan’s rugged terrain with a different goal: to spread Christianity. Their efforts bore fruit, leading to the baptism of thousands of people, including influential daimyos. For a brief period, Christianity flourished in Japan, its symbols of faith – the cross and the Virgin Mary – entwined with Japanese art and architecture. The hybrid culture of the Kirishitan, although repressed in later years, remains a ghostly reminder of that era.

Japan’s Shut Down

But the story takes a darker turn. At the beginning of the seventeenth century, Japan’s rulers became wary of foreign influence, perceiving it as a threat to their sovereignty. Christianity was banned, Portuguese traders were expelled, and Japan entered its period of sakoku, or “closed country.” However, the echoes of that initial encounter were not easily silenced. Smuggled goods, clandestine conversions and whispered stories about the distant land of “Nanban” persisted in the Japanese consciousness.

A Modern Renaissance

Curiously, the relationship was not completely severed. In the modern era, Portugal and Japan found new ways to connect. The Meiji Restoration led Japanese envoys to visit Europe, including Portugal, to learn from the Western powers. Meanwhile, Portuguese fado music found an unlikely admirer in Japan, where its melancholic notes resonated deeply with the Japanese aesthetic of mono no aware, the beauty of impermanence.

How to Travel to Japan in Portugal

Today, this transcontinental carpet can still be seen and felt, especially in Lisbon and Porto.

Museu do Oriente, Lisbon

In Lisbon, the Museu do Oriente is a testament to Portugal’s maritime empire, with exhibitions tracing the connections between Portugal and Asia, including Japan. The intricate Nanban screens preserved here depict those early encounters, filled with samurai, Jesuits and Portuguese sailors, their lives frozen in gold leaf and ink.

Alfama and Tempura

A stroll through Lisbon’s Alfama neighborhood can lead you to restaurants offering “tempura” – a dish believed to have been introduced to Japan by Portuguese missionaries. The word itself derives from the Latin “tempora,” referring to days of abstinence from meat. Although the Japanese have elevated tempura to an art form, its roots remain unmistakably Lusitanian.

Ribeira, Porto

In Porto, Ribeira is a maze of narrow streets where you can find references to “Nagasaki” or “Kyushu” in old records. Porto is also known for its vinho verde, a fresh wine that has gained popularity in Japan’s growing wine scene, proving that the flow of influences continues in unexpected ways.

Japanese Garden, Serralves Foundation

Another striking example is the Japanese Garden at the Serralves Foundation in Porto. This space reflects the harmonious blend of Japanese and Portuguese elements, with cherry trees blooming in Atlantic breezes.

The Legacy of the 26 Martyrs

Perhaps the most moving emblem of this connection is the ghostly story of the “26 Martyrs of Japan,” a group of Christians – many influenced by Portuguese missionaries – executed in Nagasaki in 1597. A monument now stands in their memory, a reminder of the sacrifices made in the name of faith and cultural exchange. This history also resonates in Portugal, where churches display relics and works of art that pay homage to these martyrs.

Shared Philosophies and Artistic Connections

Beyond the physical and historical, there is an intangible affinity between the two nations. Both Portugal and Japan share a deep appreciation for the sea. Portugal’s saudade and Japan’s wabi-sabi echo similar feelings of longing and acceptance of life’s ephemeral beauty. This philosophical alignment is reflected in artistic collaborations, from exhibitions to literature, where Portuguese and Japanese creators find common ground.

In Lisbon’s Belém district, the Jerónimos Monastery – a symbol of Portugal’s Age of Discovery – is a beacon of this shared maritime spirit. It’s a place where you can almost hear the echoes of Portuguese sailors recounting their journeys to the Land of the Rising Sun. Meanwhile, Japanese tourists – a significant demographic in Portugal – wander through its cloisters, their cameras recording, their presence a modern extension of this centuries-old relationship.

Final Thoughts

The story of Portugal and Japan is far from over. It’s written in the bustling sushi bars of Lisbon, where the locals pair sashimi with vinho verde; in the Japanese gardens of the Serralves Foundation in Porto, where the cherry trees bloom along with the Atlantic breezes; and in the countless personal stories of exchange students, business partners and travelers.

This enduring relationship, born of chance and sustained by curiosity, continues to evolve. It reminds us that history is not a static record, but a living, pulsating dialogue – one that invites us to listen, learn, and look to the future. In the words of Fernando Pessoa, the poetic soul of Portugal: “To travel is to discover that everyone is wrong about other countries.” The Portuguese and Japanese discovered each other a long time ago and, in doing so, found not just a distant world, but a mirror that reflects their shared humanity.