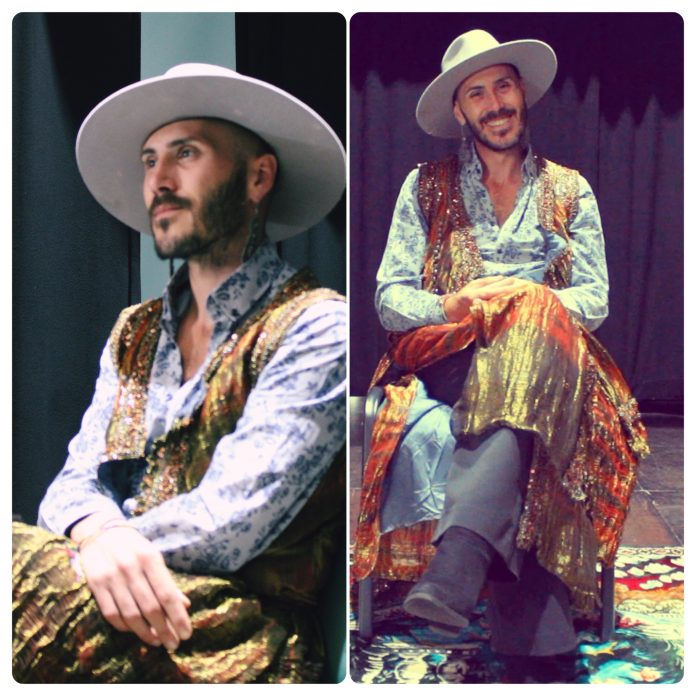

Ismael Sousa, non-binary, gay, and queer. This is how this 32-year-old identifies. But if stating this position in certain urban environments has already become more acceptable, doing it in a land where cultural, social, and demographic challenges prevail is not without its difficulties.

We talk in general about the Portuguese interior, and particularly about the Dão Lafões region in Portugal’s inland center, the land where he was born and lives. Here, we interviewed Ismael at his workplace, at Casa do Povo cultural space in Santa Cruz da Trapa, district of Viseu.

In a vibrant conversation, Ismael told us about his life, the struggle of the LGBTQIA+ community in the interior of Portugal, discrimination, and his personal relationship as a believer with a more conservative position of the Catholic Church.

Tell us about yourself. Who is Ismael?

Ismael is a 32-year-old person, born in São Pedro do Sul. He is a dreamer full of ambitions, a friendly person with an identity that he restructured and that today he is this person who presents himself here.

How has our land influenced your life?

São Pedro do Sul, where I was born, is a small town, very rural. Our land showed me this. This rurality of being in contact with agriculture and seeing the roots of life gave me a particular perspective on the world.

It made me see that the world begins here but that we cannot stop here. This paradoxical way that our land also influenced me because it showed me that we live in a tiny niche and that there is more beyond our mountains.

Regarding the affirmation of your identity. What challenges did you feel in your social and work life living in the Portuguese interior?

I came out two years ago after taking it to a level where I felt that people would respect me for who I am, not only for my sexuality. I first came out to my mother and then publicly in a television interview.

That day I didn’t dare to be in our city to face people, so I ran away to Viseu, where I lived. When I came to Santa Cruz da Trapa, I was afraid to face the stares in the church choir. But that’s when I noticed that people already respected me and that my sexual orientation wouldn’t change that, fortunately.

The process back home was easy, apart from the occasional case. Outside here, it is easier and more difficult at the same time. To be queer, even in Viseu, is still to be the victim of homophobic stares.

My personality, the way I am, and the way I dress are still odd to many. People point, talk, and behave homophobically. So sometimes it is difficult to leave here, where at least they already know me and are used to it.

How do those discriminatory looks make you feel?

Insecurity. It makes me feel like I’m doing something wrong. But on the other hand, that’s what gives me the strength to want to change and cut ties with the old mentality.

I often say that I wish twenty years from now that someone similar to me could have the openness and the safe space that I didn’t have. Even if these attacks hurt me, I always think I am opening a path for someone in the future so that other people don’t have to go through what I am going through.

If that happens, it is a sign that I have done something positive. And this is often what drives me. It is also an obligation of mine. If I dress this way, it’s because I identify with it.

I don’t do anything to upset others, but only to be true to myself and make a difference so that people realize that we don’t all have to be the same. Everyone can be whatever they want to be. This is my path, to make people understand that.

It is common to hear that Portugal is gay-friendly. Do you agree with this?

Yes and no. Yes, because we don’t see as many attacks on LGBTQIA+ people as in other countries, and also because we have some laws that defend us. However, there is still a lot of discriminatory thinking.

And we Portuguese suffer more than those who come from outside. Because those who come from abroad come but go, but we, instead, are a daily reality.

What do you think can be done for better acceptance of the LGBTQIA+ community in the Portuguese interior?

Persistence is the key. For example, if we are going to do a jazz music session and we have twenty people in the audience, we think it went wrong.

But if we repeat it, people get used to coming, to it existing and becoming part of their lives. So they start to accept it. Persistence is definitely the keyword.

Any real-life story of discrimination that you would like to share?

The day I came out publicly, I received a message from a stranger on Facebook saying that he admired me but could never do that because that would mean being kicked out of my house. It is tough to read these words.

Another case I have been following is of a young trans person who does not identify with his male body but has not yet started the transition process. This person is a constant victim of violence at school, and the actions against this in the school environment are still insufficient.

Some people oppress their orientation not to lose what they have. Others don’t leave their homes so as not to experience violence.

We usually think that the aggressor is only the one who beats, but the aggressor is also the one who does nothing, condoning this violence. We should all step in and help in case anyone sees any case of discrimination.

What is discrimination for you? Have you ever felt it in your professional life?

Discrimination is when one looks at the person, but they don’t look at their abilities. Discrimination is not giving opportunities to those who think differently because you have always done things a certain way.

As for me, I would like to say no, that I had never suffered discrimination, but that would be a lie. I suffered discrimination indirectly by feeling that my abilities and ideas were not valued in favor of other, more absurd ones.

What is your job?

Right now, my job is to be in the cultural center with its activities. I am also finishing a course as an event organization technician, which is what I did for many years but didn’t have certification for.

My work here at the cultural center is just beginning. But it is something I want to do in the sense of giving more culture. The program could be called just that, to give more culture. Because it is a cultural center that, before the pandemic, was very busy, but with the pandemic, everything went backward. Now we are slowly restarting.

I aim to have this house weekly with people coming to the theater, cinema, music concerts, and exhibitions. To try to bring a little of what culture is on its various fronts and bring the difference to Santa Cruz da Trapa. And to become cultured doesn’t mean simply to get to know things, but to get into the habit of merely going. Something that in our land is not very deep-rooted.

What are the challenges of culture in our land?

Encouraging people to come.

How can you encourage people to participate in cultural events?

When I was a young boy, I hated going to museums. I found them boring. It wasn’t a space where you could talk loudly or do anything. What I often say is the need to create different ways to visit a museum.

You can take children and get them used to going to the museum. But not just going for the sake of going, but looking at a painting and asking them how it makes them feel. And the activity can be just this. Arriving, setting up a table around a painting, sculpture, projection, and creating a debate.

You have to create this movement in museums. It is necessary to create movement in cultural centers. You must develop and train for culture and work for what the masses want and don’t want.

Because if I go to see something I want, I don’t challenge myself. But I’m forming myself when I see something I don’t want. It’s this way. It’s taking the movement to galleries, cultural centers, and museums. It’s creating activities to attract people.

This is what we need to do. We have an underused movie theater in our city, with the excuse that nobody goes. But nobody goes because nothing is done. It has to be done even if nobody goes. Eventually, people will create the habit and start appearing.

How do you position yourself as a believer concerning a more conservative position of the Church regarding homosexuality?

The Church is an essential milestone in my life. I attended the seminary in Fornos de Algodres for ten years. I studied theology, and it made me see the world differently. For many years I repressed my sexuality because of what the Church told us.

Until when in 2006, the most hated Pope in contemporary history, Benedict 16, released an encyclical called “God is love,” which shows that God is just that. He is the mother’s lap, where everything is accepted.

I thought of myself as gay. The part about becoming queer and non-binary is something that came later, over time. I started reading that encyclical, and when he wrote it, I didn’t understand it. Years later, I reread it.

I, too, like the masses, did not like him. But in 2010, I was in an audience with the Pope, and his presence marked me for life. It made me feel a lot of peace. And I started to need to know that person and began to read what the media was not reporting.

For me, he was a great pope and a great theologian. The encyclical that he wrote is a simple message that God is love.

God does not punish, and he cannot because he only loves. If the Catholic Church doesn’t accept homosexuality, it’s not doing God’s representation because God accepts me as I am.

I live in the way of love and do what Christ said when he came to earth, including the commandment to love God and love your neighbor. If the Church does not love me because of my homosexuality and labels me as a sinner, it is not doing its job.

How is supporting the LGBTQIA+ cause consistent with your religious or political beliefs?

Generalization is one of the biggest mistakes. Just because you are homosexual doesn’t mean you are not a believer. I make my way and train people in that sense.

Having twenty people in my choir, religious and some in their eighties, and accepting my homosexuality, is a good path, showing how generalizations are wrong. Just because I’m gay, I don’t have to be labeled as having a political party.

Nobody has to have a political party. This lack of freedom sometimes doesn’t fit in people’s heads. It’s the same as thinking that a priest must be from the CDS (Christian Democratic Right party).

He doesn’t necessarily have to! We have to look at politics differently. The 25th of April gave us that political freedom.

How do you feel about the growth of “Chega”?

I often say that many crazy people arrive at positions they shouldn’t. Populism is a problem of nations. It leads people to become blind. André Ventura was lucky to tell the masses what they wanted to hear.

The big problem is in the way he wants to solve these problems. That’s the big mistake. I get worried when I see “Chega” taking such proportion, and even more in our small town to see that there are “Chega” candidates.

I think about what we are doing. People are not used to politics. Politics was never taught and still isn’t. People vote for parties because their parents voted for those same parties, not considering the proposed measures.

The leader of the “Chega” party uses religion a lot, also to reach illiterate people. Illiteracy is still a big crisis in Portugal. Not only the fact of being able to read but not being able to understand.

It scares me its growth, and I think that it is the responsibility of all of us to fight against it and show that the way to solve particular problems can be different.

Do you feel a united LGBTQIA+ community in the Portuguese countryside?

This year I went to Pride in Viseu for the first time because several circumstances made me feel the need to go to the march. I’m going to tell you about a particular episode.

At the beginning of September, I went to a gala with high heels, and at the end, I went to a disco where I still had them on. There was a group of fools who decided to make fun of me. It didn’t bother me, as I got used to this, but it bothered my friends.

I needed to talk about it and go to the march and say, “no, it’s time for me to show my face too.” I think the parade is for everybody, not just LGBTQIA+ people.

Because you may have someone in your family who doesn’t have the strength to go. You have to represent and fight for tomorrow so that if I have an LGBTQIA+ child, they don’t have to suffer repression.

The march is a demonstration of our rights. Those with a public voice have to use it and not think only of their rights but of the rights of others. And this is what bothers me, those who are comfortable and don’t think about others. And this is why the community has no unity.

People don’t relate to each other. LGBTQIA+ people need to understand that we don’t have to love everybody, but we have to respect each other, to come together in the sense that we are fighting for ourselves. And to show people who we really are, not what they think we are.

And in the interior of Portugal, only the big metropolises are different. In the rest of the country, there is still a lot of fear of coming out, so there isn’t a big community.

And there isn’t because a door is closed when someone tries to look for someone to help them. People never have time. The lack of time is a problem. I didn’t have that support when I needed to know myself better.

When someone asks me for help, I have to help them so they don’t feel alone because loneliness is what kills most, especially among people in the community.

You have been studying the history of the LGBTQIA+ community in Portugal. Are there any episodes you would like to share? Do you have any famous icons that have inspired you?

Yes, there is a historical event that I am inquisitive about learning more about: the ball of Graçã in 1924. There was a Carnival ball in Lisbon where a hundred and something men were seized because they were dressed as women.

And I started looking for information about that, but there isn’t any. I got there because of Botto, one of the openly LGBTQIA+ authors.

As for icons, I started reading a lot of LGBTQIA+ authors because of Al Berto, a Portuguese author from Sines, whose writing I met at a social gathering. I identified with his writing a lot! When I first read one of his texts, I thought I was the one writing it.

Still, if one personality has influenced me the most and I have with me forever, it is António Variações. He allowed me to be who I am.

When I look at him, I think, “this man dared to destroy paradigms, and mentalities without fear, being himself.” He marked me for life, and I marked him on me with a tattoo of him on my back.

Living in the interior of Portugal. What advice would you give to someone younger who is now asserting their identity as a queer person in our land?

Always be yourself. Create your personality. Find out who you are, and don’t be afraid of what others will say. If this young person is scared of what others will say, I have got something to tell you: people will criticize you no matter what.

So, find your own soul. Don’t be afraid if you feel at peace with who you are. Diversity is so beautiful. And being part of that diversity is beautiful. Self-love is the best thing that can happen to us.

Look at this. Imagine a climb, it may take a long time to get here, but I have one thing to say, the view from up here is fantastic.