In 2008, I left my parents’ home and went to study at the University of Porto. Like many at that age, I was excited about my new life. That new chapter would mean my freedom; Learning, growing, and waking up to a bigger world than my village in the interior of Portugal.

And there were several lessons, both inside and outside the classroom. But in that new urban world, the main one would be to witness the great division in Portuguese society marked by different social classes.

And everything became more noticeable as we were going through a period of a severe economic crisis that would drag on throughout my years as a university student.

Still, while some pupils were clearly going through a difficult period, others seemed oblivious to the crisis.

I was finally living what I had learned in class theory, verifying the famous dualistic model of my country. On one side, rural and traditionalist Portugal, where economic and cultural backwardness accompanied the low schooling of its people. On the other, a coastal and modern Portugal, where people with university schooling had been at the origin of an economic and urban class structure.

And this theory was put into practice in my daily life. I remember one episode in particular. At the door of my college department, a group of students gathered to protest the increase in tuition fees, and I proudly joined them. I did so because I could also feel how difficult it was to pay for my course.

A colleague passed by, and I innocently invited her to join us because I thought our cause would be that of all students. But she promptly told us that she didn’t need to protest because her father was a doctor. She then went on with her life, walking into the apartment she was renting, unlike me, who felt lucky to have a place in a social services residence.

She was also the one who reacted surprised when I told her that I was the daughter of a builder and a factory worker. Perhaps she thought I was less gifted with inferior intellectual abilities because I was poor. But my colleague’s perplexity was also connected to the fact that at college, one could find very few people from my social background and more people from the same class as her.

My colleague then showed me something very Portuguese. She demonstrated how in Portugal, the educational system remained a space where the dominant classes, with economic power, reproduced their privileges to distinguish them from the poor.

And this is as old as our language, where specific ways of addressing people reflect precisely this differentiation of social classes.

The forced titles of “Mr. Doctor,” “Mr. Engineer,” and “Mr. Professor” carry on as being the norm. One could say this is a direct inheritance from a fascist past where most of the population was illiterate, and only a class with economic power could continue their studies and exercise control precisely through a language of detachment.

These titles continue to differentiate people, more aligned with obsolete business economic models where these words make it easier to command and intuitive to obey.

However, my colleague had yet to understand that Portugal had, fortunately, evolved. But even so, having been raised in a wealthier family, she might have grown up with certain stereotypes that dictate that poor peasants from the countryside would never make it up the social hierarchy. But if I am the living portrait of that Portugal, I am also the illustration that my colleague’s stereotypes were precisely only that.

I do come from a poor peasant family. Both my grandmothers were illiterate. My maternal one had seven children at a time when this number was welcomed because it was seen as another workforce in rural life. Unlike my grandmother, my mother studied for six years and started working at twelve, at a time even harder on women who had even less the right to continue in school.

I was the first generation of my family to go to university.

But comparing classes. My colleague’s family had reached that level way before us. While my mother had insufficient schooling, my colleague’s parents had already studied in higher education, indicating that they belonged to the upper class. She and her family were thus a generation ahead of me. But she and I were there, together, in the same classroom.

Perhaps our parents would have been born in the same decade, in the sixties. But more than the time they were born, the question would be more accurate if it asked where and in which class. The chances of being born in the interior and in a poor farming family were high. In turn, the ones born on the coast had more chances to be raised in a wealthier industrial bourgeoisie, where access to education was more achievable.

But by 2008, Portuguese society had long moved away from the Portugal of the sixties. The interior became vacant, farmers fled to the industrial centers on the coast, and the old folks of yesteryear stayed behind. But don’t let yourselves be fooled, the coast of Portugal also struggled.

Between 2008 and 2014, Portugal appeared a lot more uniform than many might have thought.

The 2000s had already started economically stagnating after the fever of the 90s of rampant construction and uncontrolled financial credit. And in 2008, Portugal was undergoing deindustrialization, a process happening in a country that had never been prosperous in the secondary sector.

By then, Portugal was facing a severe debt, witnessing unemployment soaring, causing my generation to graduate and seek a better life abroad. As a peripheral and forgotten country, Portugal was more on the opposing side of progress.

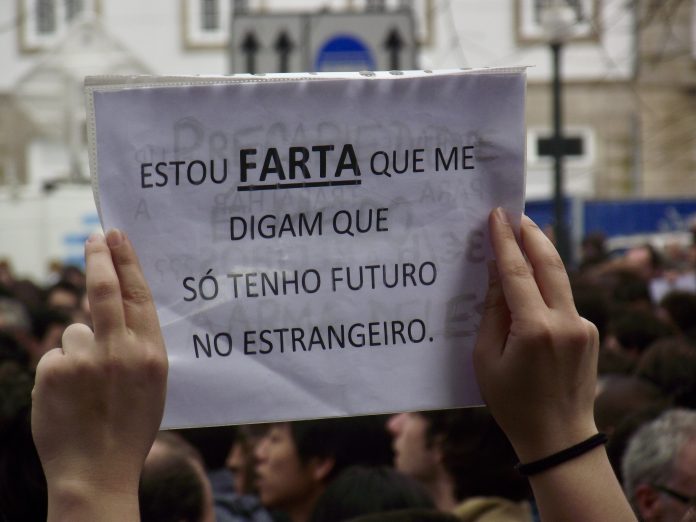

In 2011, the social situation reached its peak, and on March 12 of that year, summoned through a Facebook event, thousands of people took to the streets, non-partisan, calling for a better Portugal, desperate for the lack of perspective and a future in Portugal. It was the largest protest on record since the Carnation Revolution with the end of fascism.

But like several trajectories of the modern era, nothing availed them in a year of political right turns, the entry of the IMF, and a policy of austerity that has never ceased to exist in our lives until today.

As time went by, we were suddenly helped by the tourism boom to help us from the crisis we lived in. And for a brief time, the weight of social classes seemed to have diminished. Scholarships returned to students; on the outside, Portugal finally seemed to be making itself known to the world. But while this was happening, low-wage jobs continued, particularly in tourism, of which I was part.

Not having any financial support from my family, I had to submit myself to earning the minimum wage of 640 euros at the time. It didn’t help that I had studied; the precariousness that plagued our lives was widespread, and having a college degree was no longer synonymous with wealth.

I felt I represented most of the Portuguese population, someone living paycheck to paycheck.

Portugal may say it breathed a sigh of relief for a while, but perhaps the poorer and working classes never felt that coming. The Portuguese present reveals how we are closer to the rest of the world and how everyone is experiencing difficult days. Our days have been marked by an inflationary crisis, continued low wages, and a problem of speculation in the real estate market.

This last one has constantly been making the news. It has been one of the many stressful issues for Portuguese families, causing many university students who cannot afford a room in our cities, be it on the coast or in the interior, to drop out.

This crisis is different. If Portugal was forgotten before, now it has become an oasis for millionaires who are crushing the middle class for good. This is evident everywhere, in Porto, Lisbon, or small towns.

Portugal seems to be reversing the march of equal access to education and the disappearance of that fine line of class difference. It feels like we are going back to a time when the poor couldn’t afford education, dropped out, and started working, while the rich were able to continue their privilege of education and social ascension.

The conclusion is that classes and their differences never ceased to exist, and breaking the cycle of poverty is a great challenge in an increasingly unequal country.